In excited support of the release of the

fabulous new book ‘Organise Ideas’ from Oliver Caviglioli and David Goodwin, I

am sharing some of the various ways I have used word diagrams in my own

practice. I hope these posts will be of particular use to

teachers of economics and business, but also more widely!

Why use Venn diagrams?

Venn diagrams are simple, quick, efficient and easy.

Students can get started on comparing two things within a matter of seconds.

They are ideal for clear, visual comparison and students can usually, assuming

some reasonable recall of knowledge, easily identify a list of features of at

least one of the things. They can then check down their list to see if each

feature is also a feature of the other thing and thus decide where to write the

feature on the diagram.

Why is it useful for students to make

comparisons in their retrieval practice?

I often need to teach students about concepts that have a

partner pair; demand and supply; free market economy and command economy;

indirect tax and subsidy. These partner pairs are typically very similar, but

with some opposite features. I regularly engage students in retrieval practice

on the individual concepts (e.g. ‘define the term free market economy’ or ‘draw

a diagram showing the effect of a subsidy’).

However, this can get a little boring after a while and,

once content has been ‘rote learned’ and ‘automated’, the advantages of further

simple retrieval tasks begin to diminish. Therefore, I like to introduce

retrieval Venn diagram comparison tasks to challenge students to think harder

about recalled concepts and to develop more connections as a form of

elaboration.

The theoretical basis for this suggests that elaboration

‘multiplies the mental cues available to you for later recall and application’

(Brown et al 2014). Thus in offering this task, I am trying to encourage creation

of multiple linkages within and between topics so that there are more mental

‘routes’ to get to a concept and thus increased chances of students remembering

that concept. Weinstein et al (2019) also suggest that explaining similarities

and differences, as part of elaborative interrogation of topics already studied,

is beneficial as ‘you are making connections between old and new knowledge,

making the memories easier to retrieve later’.

How do you use Venn diagrams for

retrieval practice in the classroom?

1.

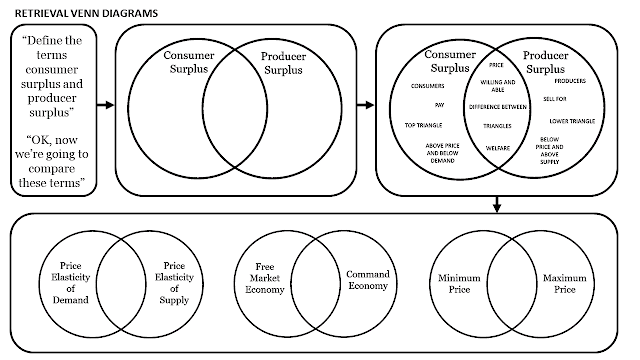

As a warm up, I would typically provide students

with a very quick and basic definition retrieval task (e.g. defining two

similar concepts that I am fairly sure, from previous successful retrieval

attempts, that they all know e.g. producer surplus and consumer surplus).

2.

I would then display two overlapping circles

with one of the retrieved concepts labelled in each. I would provide examples

of similarities and differences between the concepts and write them in the

appropriate places on the diagram.

3.

Next, I would (without the initial definition

retrieval this time) display two new overlapping circles with two new concepts

(e.g. PED and PES). I may work through this collaboratively with the class

(taking answers from students) and then…

4.

..set further tasks with even more new concepts

as individual work, or I may just skip straight to the individual work.

5.

After individual thinking time on each task, I

would encourage students to verbally elaborate on the similarities and

differences they have noticed and recorded in order to check, correct and give

feedback as required.

6.

Depending on the complexity of the concepts

chosen, I may or may not set further rounds of individual tasks.

Where can I read

more?

There are further details on the construction and use of Venn

diagrams (and many other diagrams!) in Oliver and David’s book as mentioned

(see details below). The book also contains a case study from Nicky Blackford

on her use of a Venn diagram and advice from Kate Jones on using word diagrams

in retrieval practice more generally.

Please see Kate’s three books on retrieval practice for lots

more theory and practical tips on that topic too!

References and Further Reading

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L., & McDaniel, M.A. (2014).

Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning.

Caviglioli, O. & Goodwin, D. (2021). Organise Ideas: Thinking

by hand, extending the mind.

Jones, K. (2019). Retrieval Practice: Research and Resources

for Every Classroom.

Weinstein, Y., Sumeraki, M., & Caviglioli, O. (2019).

Understanding How We Learn: A Visual Guide.

Comments

Post a Comment