Retailers have used your loyalty card

data to analyse your typical basket. Fashion, leisure and car companies have

tracked your browsing of their website to measure your engagement. Your fitness

app is keeping tabs on what you’re up to, Facebook is noting what you’re

Googling, even Teacher Tapp will chase you if you’ve gone AWOL for a while![i] You’ve been tracked,

segmented and targeted with all manner of very specific messages from numerous

different sources.

And the purpose of this data analysis

and precisely targeted messaging? To attempt to affect your behaviour.

My favourite haunts are not dropping

me a line about the number of loyalty points I’ve accumulated because they have

a duty to report to me, they are trying to get me out of my house and back

through their door. My exercise app is not reporting my weekly activity total

because they have an obligation to do so, they are trying to give me some

praise to keep me going and get me logging in again. And when I’ve not done any

activity, of course they know, but they don’t tell me that at all, they try

instead to lull me back with some friendly and gentle encouragement.

Communication here is about building a

relationship. And relationship is about changing behaviour. Behaviour change

makes things happen.

And when they’re considering the data

in their possession and how to use this to communicate with me, these

businesses are not just sending me a ‘cut and paste’ of whatever data they have

about me. They’re not going to send me a message containing raw data that is

going be badly received by me or will fail to promote actions consistent with

their desires. They’re not deciding when to contact me based on what’s

convenient for them, expect maybe to say that they’re also not going to notify 1000’s

of customers of a problem at the same time, unless they’re properly prepared to

field them calling up their call centre. They’re not going to waste time and

money contacting me by email at all if I am not engaged with their

website or if I don’t typically open their messages.

They are thinking deeply about me,

about exactly what I message should hear, about when and whether I will

listen, and about what I will do with what they tell me.

When done best, high quality CRM will

ensure every communication is sophisticated, intentional, personalised, efficient,

effective, and focused on building the relationship.

So what if we reframed our approach

to home-school communication with this mindset? Reporting to parents[ii] is thus not seen as a

burden, a statutory duty or a workload issue, but an opportunity for

communication. An opportunity to build a relationship, to change behaviours and

to make things happen.

What if we reinvented reporting? What

if we starting thinking about fine tuning home-school communication based on

meaningful data that precisely targets messages to promote desired behaviour

change? What if we changed our thinking around reporting to ensure it is

designed for relationship building? What if we moved beyond sender-focused

considerations and instead designed our systems with a more sophisticated and

considered receiver-focused approach?

OK, so I shall assume you don’t

currently have a large team of highly paid and well-resourced data science and CRM

professionals at your disposal. I will also assume you don’t currently have highly

complex data tracking, storage and analysis ability to enable you to monitor

website interaction, email open rate and VLE engagement of students and

parents. (Be fascinating if you did have all these things, but let’s stay

rooted in some kind of reality!!).

What could be realistically be considered

in rethinking reporting for the current era, within the obvious resource

constraints that apply to most school environments? This blog takes inspiration

from the world of CRM and explores five possible principles for home-school

communication and reporting.

The Data Fad Phase

In schools we have been awash with

all manner of data, but maybe the real missed opportunity throughout our ‘data

fad phase’ was failing to use data to inform and target communications

effectively and failing to use it develop relationships. Maybe we have instead

just churned out the raw, often numerical, data we’ve collected without deeply

considering it from the receiver perspective. As a duty, a box tick. A broad

brush, mass communication and, sometimes, brutal approach. The numbers have

become the end game, instead of the tool. Some warped uses of data

(particularly with regards to reporting progress) have also sprung up.

We’ve no doubt told students (and

their parents) who woefully underperformed at KS2 that they’re now ‘on track’

to meet the low GCSE expectations we’ve subsequently formed of them. We’ve

invented seemingly scientific micro measures of a half-term of ‘progress’ and

delivered home highly complex reports about these fallacies. We’ve sent parents

‘current attainment GCSE grades’ when students have barely even begun courses,

or even whilst they’re still at Key Stage 3. Did we even need to send any of

these numbers? Were they always helpful? Have they, at times, caused harm?

Principle One - One cheap and easy change to reporting is to instantly

stop collecting and stop sending raw data that isn’t useful, isn’t reliable

and/or doesn’t make sense.

Reporting implications when the curriculum is ‘the progression model’

But now the pendulum swings the other

way, curriculum is now the much quoted ‘progression model’. And thus we’ve

thrown out the progress data in some quarters and rapidly arrived at

alternative conclusions as to other numbers (or something else) we need to collect

and send home instead. Removal of progress data and progress reporting creates

a vacuum, and we need to be careful to think deeply about what fills the void.

After the careful sequencing of

knowledge and skills in my curriculum planning, I’ve subsequently grappled

myself with the realisation that sending home a grade early in a course makes

little sense (it likely never did) as I’ve not even attempted by this point to

teach students to do anything in terms of many of the skills they’d need to demonstrate

to achieve higher grades. All I will have had a proper opportunity to teach (and

students to realistically learn) in early weeks and months is some conceptual knowledge

and some low level application. But, honestly, if students know these things

and can do the simple things I’m asking of them right now, then they are ‘on

track’ in my intended curriculum journey. It’s quite difficult for me to accurately

measure that, and even more difficult to clearly communicate that. Yet I do

have a clear concept in my mind of what ‘better’ and ‘worse’ at this early

stage looks like, and what these will look like later, and at the end.

And thus (as impending Year 10

progress check points drew closer) I rather rapidly found myself caught up in

an impossible quest to supply a perfect reporting replacement for these ‘fake’ early

course report grades. Raw marks, percentages, ranks, tables, words and graphics

have all undergone my scrutiny (and been the subject of debate from others in

the field - thank you to all who have generously engaged in answering my

questions with your views on these matters!). I will spare you the full

analysis, but here are some headlines.

I like ranking due to the connection

with the logic of comparative judgement and the ultimate likely ‘bell curving’

of final results, but there’s little good news in being told in such brutal

terms that you’re at the bottom of the class, especially very early on in a

course. Ranking creates a very explicit competition between students, rather

than a competition against a standard or against a previous personal best, and this

is something I have been trying to avoid in classroom (not least taking into

account recommendations from Mark Roberts[iii] about avoiding

competition to benefit teaching of boys in particular).

I like raw marks, as they represent

exactly what was and was not awarded, but these are really difficult to make

sense of and compare across a range of 8-10 subjects with different assessment

types. And we must consider that (as much as we might want parents to support

improvements in everything, and care about our subject in particular), with

limits to the time and resources available, parents are specifically looking to

identify outlying and underperforming subjects where the student might need a

particular push. Raw marks also become difficult to compare over time,

especially in hierarchical subjects where students should score higher in

earlier foundational content tests, but will struggle later as the bar is

raised higher.

I tried tables displaying

attempted/unattempted topics of a course, with raw mark or percentage

completion statistic in each attempted topic cell. I tried graphical bar charts

of notional ‘completion’ of various skills. Whilst doing a nice and simple job

of visually conveying ideas of attainment and progress on my curriculum

journey, I didn’t like either as a parent who did want to know if this was

‘good enough’ and how it compared to how everyone else was doing (the only way

out of this was making them look like horribly complicated data dashboards).

Percentages came out high for me (and

seems to have garnered support from others out there who are doing great

curriculum thinking). I like the potential for easier subject-to-subject

comparison, although I felt they still needed some context. One idea popular in

schools who have gone this route was to combine with cohort average, although

this was neatly tainted by one person I spoke with who pointed out I would be

telling almost half the cohort they’re below average, which (whilst unavoidably

true!!) doesn’t sound great. The potential solutions (such as comparison to

various quintiles or deciles etc.) only serve again to create rather

complicated reports which would end up requiring a sound understanding of

statistics to make any sense of at home!

But only when I began to consider

what receiving a percentage as a parent and student would mean from the perspective of different types

of students and parents did my thinking begin to further unravel and

then finally move forward to some kind of resolution. Viewing things from the receiver

perspective as a broad concept is an approach inspired by blogs from

Professor Becky Allen (linked below[iv]), where she details her

thinking around the psychology of how what we tell students might affect their beliefs

and actions. I will return to further consideration of this later!

Principle Two - Consider the likely reaction of and desired action from

the receiver. How will reporting communication develop the right relationship

with the student and parent in order to secure behaviours that promote high

attainment?

Receiver-focused Reporting Part 1 – What do you want students and

parents to think?

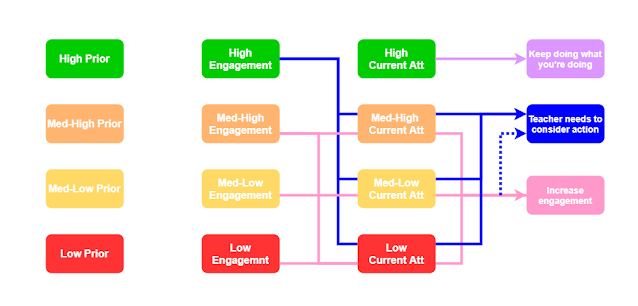

I will spare you the huge table of

thinking that followed as I tried to put myself in the position of teacher,

student and parent of different types of students who were given a percentage current

attainment report (e.g. Maths 46%, Geography 68%, etc.). I considered the

perspective of those from different levels of prior attainment, different

levels of current attainment and different levels of ‘effort’ (the list of

assumptions accompanying this table began to grow of course also – ‘assume

prior attainment measure is reliable’, ‘assume current attainment measure is

reliable’, ‘assume I could actually measure effort!’). Crudely simplistic

‘high/medium/low’ labels were used for prior attainment, current attainment and

current effort. Essentially I ended up identifying a number of different student

‘segments’, to use a CRM term (e.g. ‘High Prior Attainment/High Effort/High

Current Attainment’ was one segment, ‘High Prior Attainment/Medium

Effort/Medium Current Attainment’ another etc.).

It quickly became clear that

receiving a result of, say, ‘60%’ would mean different things for different

students. For those with previously high attainment (e.g. notional 80%) this

represented a drop in performance, and the picture (and required actions to

redress this) depended heavily on how much effort the student had applied. High

prior, low effort, lower attainment meant the student probably needed to

pick up their effort (or at least try that!). High prior, high effort,

lower attainment needed to be addressed by the teacher really though, if the

student was trying hard as they could, something had potentially gone awry with

something else that was out of their control! This felt like it needed

acknowledgement in the communication, as part of building the relationship

(i.e. ‘we can see you’re trying really hard and doing all we’re telling you to

and all you can, we’re looking at this from our end too’).

For those with low prior attainment

(e.g. 40%) and high effort, 60% represented a superb improvement in performance

and would be potentially worthy of praise. For a middle prior attaining student

(e.g. prior 60%), 60% represented a maintenance of performance. But what if

their effort was really low? Is this OK? ‘You’ve always been a bit lazy and not

fulfilling your full potential, you still are, but hey, just carry on!’ What if

their effort was high though? Does everyone just settle with that, or should

the teacher be evaluating whether there is still something that could be done

to translate this high effort into high attainment?

A percentage without context could

not convey the messages it needed to and was widely open to interpretation. It

wasn’t just as simple in reality as ‘100% is perfect, 0% is nothing, and

anything in between was somewhere more or less in between’, as my ‘curriculum as

the progression model’ mindset would have me believe. And again, comparison of

these percentages over time (with differing levels of assessment difficulty)

became problematic.

So, unless you know otherwise, I have

resolved that there is no perfect and simple attainment measure that can be

used to convey ‘all things to all men’.

Receiver-focused Reporting Part 2 – What do you want students and

parents to do?

What was apparent in my table of

student segments though, was some elements of repetition. (This thankfully rendered

my initial ‘identify desired action target for each segment cell’ approach

redundant as I moved my attention to a more streamlined logical link from

segment to desired action). There were 3 broad categories of ‘desired thinking

and required action’ resulting from anyone’s prior attainment, current attainment

and current effort combination.

-

Student needs to do more (try harder)

-

Student needs to keep doing what they are doing (in a broad sense,

obviously they will need to keep doing new and more difficult things, but all

indications thus far are that they should continue to follow instruction and

engage in the manner with which they have done thus far as this has ‘worked’ )

-

Teacher needs to do something (student is trying as hard as they can,

but things are not ‘working’).

Segmentation, with words

After some further wrangling, I

scrapped the percentage figures all together and moved to words alone. These

are easier to understand and easier to compare than any numbers. Implications

around broad correlations to any grading can then be made loosely, or left to

be implied.

I determined that using 3 category

levels (high, low and med) was not satisfactory, so decided to split out to 4

(splitting med into med-high and med-low). This was beginning to look rather

similar to the suggestion of grade quintiles from one generous contributor to

my thinking here (they liked quintiles as they ‘hide the noise’ from

percentages, which makes a lot of sense), although I am keen to remove the link

between attainment and grades, plus this more generic approach can also be used

at earlier stages in the education system too (promoting consistency across the

system and better system-wide understanding). I could be easily persuaded to

move to 5 categories instead of 4 (adding a ‘very high’), but I wouldn’t define

these as quintiles or quartiles in my approach, as I will be selecting the category

boundaries, and there will not necessarily be equal numbers of students in each

category.

Subjectivity in determining attainment categories

Broadly, the current attainment

categories would be determined something like this (some adjustments/flexibility

would need to be made in context – for example if your cohort typically scored

70% 7-9 GCSE and 100% 4-9, then you would not bell curve across all grades as

your likely profile will be different to the national picture. If you’re doing

this for Year 9 French it will be different for Year 13 sociology). These are

rough ideas, I know these don’t compare and have holes, keep reading.

High attainment – 70% plus in cohort, grade 7-9, high B-A*

Med-high attainment – 50-69% in cohort, grade 5-6, C to med B

Med-low attainment – 30-50% in cohort, grade 3-4, D/C

Low attainment – 0-29% in cohort, grade 1-2, grade E and below

A subjective judgement call

does need to be made here at subject level of what counts as

high/med-high/med-low/low attainment. People will potentially criticise the

lack of consistency in the background here, but it must be born ultimately in

mind that the sole purpose for the

attainment word choice when collecting data for reporting is to facilitate

segmentation and thus to determine the appropriately recommended action for

targeted communication. So if the whole cohort is performing way below

national average, then no-one should be marked as ‘high’, as we don’t want to

ultimately communicate ‘all is fine’ for the top student, simply as they are

better than the others around them (they could be supported to improve in order

to attain highly when nationally compared). Furthermore, if the whole cohort

has scored 80% plus on the assessment, we don’t necessarily want to suggest

that everyone is ‘high’ attaining because we’ve got restrictive centralised percentage

boundaries in place that don’t make sense on assessments that differ in

difficulty (This matter is addressed later also).

I accept this is a somewhat messy

position, and won’t receive support from everyone who wants technical/scientific

perfection, but this is functionally pragmatic. The decision is based, as best

as we can, on what we want to tell receivers in order to (hopefully) affect

what they think and what they do in as useful a way as possible.

I don’t like the predictive and goal/expectation

setting idea of using targets based on prior attainment at individual level.

These approaches essentially project forward in numerous unhelpful ways (as

heavily covered elsewhere in many blogs on problems with flight paths and

target grades in general) in order to enable current attainment/progress to be

compared to what might be expected.

Providing just prior attainment

itself though, described in words, without adding the projected element,

enables comparison between what happened before and implies how current

attainment (and thus progress and ‘acceptability’ of current attainment) might

be usefully viewed, without laying in prediction, linear assumptions or

expectation. The expectation for all can remain high (as the top grade),

but the implied comparison for a student who has already history of very low

prior attainment (especially one with high effort) can help ensure a careful

and sensitive approach, without going to the other extreme and saying low

prior/low current segments are ‘on track’ and thus ‘OK’ or even ‘good’. How

exactly you categorise the prior attainment (and exactly which prior attainment measure/s you use) is likely to be subject to the same

subjective judgement as described above for the categorisation of current

attainment. It is important to recognise how the exact translation of this to

word categories might end up affecting beliefs around how current attainment

now compares to prior (more at the end on that).

Over time if would also be interesting to add ‘prior effort’. If, for example, a student didn’t try especially hard at

KS2 SATS, and perform med-high, maybe if they tried for GCSE they could

actually hit ‘high’. If a student is rated ‘very high’ for GCSE effort and yet

scored ‘med-low’ GCSE attainment, this needs different action. Either there are

issues with the curriculum (if full engagement with it doesn’t generate high

attainment) or a recognition that this student might struggle with some aspects

learning or memory

Replacing ‘effort’ with ‘engagement'

I also decided that I couldn’t

measure ‘effort’. This was far too vague and internal to the student. They were

the only ones who could really assess that, but self-assessment of that was

likely to be rather unreliable as the sole measure in the context of reporting

to parents! The best proxy for effort though was task engagement. This is

measurable (or at least conceptually so) and actionable. Measures would include

class task completion, homework completion and engaged/on-task behaviour. Essentially

if a student was doing everything asked of them, fully and properly, then

engagement is high. If a student is missing out class tasks, purposely

off-task, failing to complete all homework – they are not engaging fully with

what the teacher is setting and requiring in order to follow the curriculum. Essentially,

the purpose of this is to clarify the message for parents, answering the questions we often seek as parents from reports; 'are they doing ‘enough?’', 'could

they do more?'.

Very High effort – could not ask more. Full homework and classwork completion

and engagement.

Med-high effort – most things done – could do a bit more.

Low effort – missing some homework, not doing class tasks as well as

could.

Very low effort – no homework, no/very little classwork, disengaged.

The logic of 3 broad messages for action

Here is (after abandoning an attempt

to map out lines with all the possible combination segment possibilities!) is

what my thinking ended up looking like.

My logic goes as follows:

-

Regardless of prior attainment, or effort, if a student is high

attaining, then essentially, everything is fine! They can just keep doing what

they are doing in terms of engagement (in broad sense, see above on this and

also below on next steps).

-

Regardless of prior attainment, if a student wasn’t operating at the

high engagement level, then the most obvious logical step for them was to

engage fully.

-

Regardless of prior attainment, and of current attainment, if a student

was at the high engagement level then nothing more can be asked of them! If

they are judged to be doing everything asked of them in full, the only way any

additional attainment gains can be achieved is if the teacher can provide

different tasks to achieve this.

Obviously this is somewhat of a

simplification, but additional nuance could be added when writing actual action

statements for communication to ensure they read right for the High Prior/Low

Engagement/Low Attainment segment compared the a High Prior/Med-High

Engagement/Med-High Attainment segment. (You can add more detail with 5

categories instead of 4, as you generate more segments).

Further curriculum-related ‘next

steps’ actions would also of course be needed to continue to propel progress,

especially for those who need to ‘keep doing what they’re doing’. This

shorthand that I have used of course really means, ‘keep doing what the teacher

is telling you to do and what you’re doing in terms of your broad approach to

and engagement with learning’, but what the student will actually need to do

over the coming period will be different to what they did in the last as the

journey will continue to move forward (e.g. the student might have smashed 100%

in a knowledge assessment as they have followed every instructional step to

perfection, but over the next sixth months they next need to develop analysis,

so the next steps in learning will involve new sorts of instructional steps

that they will need to continue to follow to perfection keep operating at

100%).

What could reports look like?

Here is mock-up of what a report might

look like for a student. (I’ve just quickly scrawled the actions, but you get

the idea - you could easily give the categories more appealing titles of course also).

Geography

Prior attainment: Med-high

Task engagement: Low

Current attainment: Med-high

Action: Try to increase your engagement in set

tasks as you might well be able to improve further. This means completing

all homework, completing classwork to the best of your ability and trying your

hardest to improve.

Next Steps: (Here would be something about the next

topic coming up or next steps for specific geographic skills)

French

Prior attainment: Low

Task engagement: High

Current attainment: Low

Action: Continue to try hard in your work. Your

teacher is going to work with your to try to help you improve your attainment

further as we can see you are trying hard and we’re here to help you achieve

more!

Next Steps: (Here would be something about the next topic

coming up or next steps for specific related to speaking/listening skills etc)

Maths

Prior attainment: High

Task Engagement: Med-high

Current attainment: High

Action: Well done, your work so far has meant you

have reached a high level. Keep up work in this subject, do pay attention to

your task engagement though if your marks begin to slip as there is still some

room for your to engage more fully in order to improve further.

Next Steps: (Here would be something about the next

topic coming up or next steps for maths practice)

Best of a Bad Job

This is not still perfect.

The primary issue with assessing and

reporting on a carefully sequenced hierarchical curriculum is that student

attainment could potentially ‘drop’. Many students should be able to achieve

high scores on an early assessment (e.g. early in a GCSE course when assessment

is simply on basic and foundational knowledge which all students should be able

to grasp) but as the content becomes more challenging, and more challenging

demands are made in terms of skills, later assessments will be more difficult.

In an ideal world, all students would make ‘optimum’ progress and continue to

achieve ‘full learning’ and high scores on these more difficult things. Reality

and experience does seem to indicate though that having every student continue

to be able to do everything to perfection might not be realistic. And

therefore, the attainment results of a student who performs well early on in

terms of knowledge but less well in terms of analysis/evaluation/application later

on will appear to fall in attainment over the course. This drop doesn’t look or

feel good (particularly because it runs so contrary to our existing notions of

‘progress’ and how we attempt to track, communicate and affect it).

Potential solutions to this issue:

-

Seriously intense effort made with students and parents to communicate

the nature of the curriculum so that decreasing attainment is not always

necessarily seen as poor progress as such, but more as the bar continually

being raised higher and higher. This is a large undertaking and requires sound

curriculum understanding from all parties. This is not helped by the fact that

not all subjects are hierarchical, and thus the journey is not going to be the

same across the board. Expecting all students and parents to appreciate the

particular ‘shape’ of every curricular journey is quite an ask. We’re not

necessarily even there as staff in this respect, as we try to understand

subject domains outside our own, and well as just about getting to grips with considering

our own in theoretical terms. This could be disguised by capping top end attainment for early assessments at, say, med-low (as the assessment was of simple content), but they your 'high prior' parents and students will be seeking what has gone wrong, and the answer will be 'nothing'. (This type of cap would not work with my receiver-focused logic outlined above either, just as a side point).

-

Regarding this drop exactly and deliberately as ‘inadequate progress’

and setting the expectation that the teaching, learning and curriculum will

enable students who are applying maximum effort to continue to attain at a high

level throughout and to the end. Truly embracing high expectations for all with

no allowance of the notion that some may ‘not be able’ to achieve the highest

attainment. This is the definition of setting the bar high for all. It is an

excellent ideal. It is poorly aligned with our bell curved final national

outcomes though which makes it a very tough conceptual sell as students and

parents know that not everyone can get the top grade in the end.

-

Bell curve all data to reduce chances of this ‘drop’. This does assume

that the ‘top knowledge achievers’ go on to become the ‘top analysers’ though,

and the ‘lower knowledge achievers’ will fail to analyse, which is not always

the case – slightly lower effort but high prior and med-high current attainers

may be able to maintain med-high performance compared to high effort, low

prior, high current attainers).

-

Delay all attainment reporting until much later in the course. This

would remove the appearance of a drop. This could be done by simply not

reporting to parents as regularly in such ways, or by removing the attainment

data from the report, and simply reporting engagement and action required. This

approach has the most merit in my opinion. Reporting is therefore ‘action

focused’ during early phases (i.e. mid-year reporting). Only when meaningful

summative data has been collected should attainment be reported. (Oddly, this

then ends up potentially facilitating reporting with grades if you still really

want to do that. If you’ve reached a point where sufficiently challenging

content has been covered to enable a consistent and trackable assessment that

won’t drop, you have also likely reached a point where you can bell curve and

generate something approaching grades (or least broadly so anyway if you have a

large cohort). Maybe grade quartiles or quintiles would be a good move at this

point potentially, as the aforementioned person I spoken to on this had indeed proposed.)

Final Proposal for Reports

Mid-Year Report

Business

Engagement Level: Med-low

Action: Increase your engagement in

set tasks and you are likely to be able to improve further. This means

completing all homework, completing classwork to the best of your ability and

trying your hardest to improve.

Next Steps for the Coming Months: Complete

all weekly retrieval practice tasks set on all topics in the first unit in

full. Ensure you complete all Google homework quizzes set in full.

French:

Engagement Level: High

Action: Well done – your teacher is

really pleased with your full engagement with all homework and class tasks.

Continue to follow their instruction and you will be highly likely to achieve a

high attainment mark as the end of the year. Talk to your teacher if you feel

you could, or would like to, be doing more towards the subject so they can advise you.

Next Steps: (Something specific

relating to French over the coming months)

Year-End Report

And then at the summative, end of

year stage, the reports would also contain prior and current attainment level

for comparison (as shown in my mock ups above).

Principle Three – Focus reporting on using data to identify student

‘segments’ and communicating carefully crafted and precisely targeted actions

for different segments relating to behaviours that can be changed, noting how

and by whom. Only communicate numerical attainment data if it makes sense to do

so.

Receiver-focused Reporting Part 3 – How and when you communicate with

parents?

If schools are sending reports home

by email (or on paper) at the end of days and/or the ends of weeks and/or the

ends of terms, this does not facilitate easy reaction, action and contact from

student and parent. Parents may want to discuss reports with teachers and,

speaking as a parent, it is not always helpful to receive school information

immediately prior to a holiday as I can do little about it when my child is

winding down for a break! The report is forgotten and the new term/year begins

with little change.

Schools could more carefully consider

when would be a good time to receive information as a parent and as a student

with regards to when they would be most motivated and able to take action.

Scheduling parents evenings specifically to provide the opportunity for

conversations about written reports can help, as can scheduling of class time

to discuss data and actions with students. Providing the written report at the

parents evening might also be an option if parents are not engaged with email

or postal communication.

It would be interesting to examine

the impact of sending mid-year reports home at the beginnings of weeks/terms with

regards to attention paid to them and the take up of new actions as a result of

them.

Schools should also evaluate their

approach to reporting and to other personalised non-report communications. Are

there any communications outside the normal reporting framework? If so, are

these:

-

Effective? Are they getting through? What is the ‘open rate’ on emails

in a sense? Is there any response or action following contact with home? Does

it change anything? If communications are not getting through or having any

effect, then these need to be changed to avoid wasting staff time and to ensure

actions happen!

-

Motivating? Are communications focused on things that can be changed and

actions required to secure change?

-

Actionable? Do parents and students know how to carry out suggested

actions? Do they have the resources required?

Principle Four – Consider the receiver with regards to time and manner

of report communication. Analyse communications for effectiveness and make

changes if communication is not affecting behaviours and making things happen.

Schools could consider heading off

some later issues of underperformance by early identification of engagement

issues. In the same way as my bank contacted me about impending risk of

entering my overdraft due to low funds and an upcoming scheduled payment

(prompting a rapid transfer of some cash from my savings to resolve the issue

before it even became an issue) schools could pick up quicker on early signs of

low engagement and act fast to build relationships that can foster action to

increase engagement before the impact is seen on attainment.

These messages should be considered

carefully. In the same way as my exercise app prompts and cajoles me gently

back into the fold, we need to mindful of the motivational impact of our

communications at this stage. What might be good and worth reporting on the

positive side (100 achievement points!), might be less good on the negative

side (100 behaviour points!) and maybe a non-numerical communication of a more

positive/inspiring tone needs to be chosen in some situations.

Principle Five – Different behaviours warrant different types of communication.

Design bespoke communications and be prepared to communicate at unscheduled

times to affect and encourage desired behaviour.

Further cans of worms

As with many other aspects of

education, the answers here may not always be black and white, be clear cut, or

even exist, but we have to make some decisions on how to proceed in the end,

and thus (in the absence of sufficient research or perfect solutions) it is

important to consider the potential implications of our current actions and investigate

novel ways in which we might be able to secure some low cost, marginal

improvements.

I would strongly recommend that you

also read blogs linked below by Professor Becky Allen and David Didau[v]. David explores issues

around target grades and what the 'curriculum as the progression model' means

with regards to assessment in more detail.

Becky explores further the impact of

what we tell students with regards to their attainment (especially vs cohort) on

their actions. She helpfully describes the ‘grading games’ we are trying to

create and the likely actions that students will take on receiving positive or

negative surprises (this appears to be, from I see from Twitter, to have been the

subject of her researchEd Surrey talk also, which I am disappointed to have

missed!). This provides a hefty challenge to the implication in my approach

that simply telling students and parents that Jenny is ‘not trying hard enough’

and ‘is not yet achieving at the highest level’ will actually generate the ‘try

harder’ behaviour we are hoping for. Jenny may well decide that she is doing

fine where she is thank you very much and the effort required to increase

attainment just isn’t worth it. She might even do LESS if her positive results

show she has overdone it compared to her own goals!

This is a significant problem. It’s

not exactly easy to solve though, what should we do? Try to collect student

thinking on their goals and expectation prior to reporting and then

artificially adjust our reporting to manipulate their thinking?! Yikes! (No-one

is suggesting that by the way!). Becky is also careful to point out not just

the risks in sharing cohort-referenced data, but also the risks in NOT doing so

(Freddy could happily press on, blindly unaware that he won’t be able to secure

grades for college entry, unless something changes if we don’t ever tell him

where he is at).

Unfortunately I do not dispute

Becky’s points (!), I just don’t necessarily know what to do about them! I have

made a judgement call here in this blog on the design of my preferred ‘game’,

but I would certainly not suggest that it’s perfect. I do feel however that we

are both very much aligned in the principle of deeply thinking about the receiver

when designing assessments and reports though. So this must be where the

furthering of thinking continues. How

can we use what we know from our data to more effectively segment and communicate

in a way to actually achieve the desired actions/behaviours we want to see?

The issue of risk of

cohort-referencing (even if only implied by the high/med-high/med-low/low

words, rather than being as blatant as rank) that Becky highlights is the

biggest problem I have yet to identify in my own suggested year-end reporting

approach. Although it is not a problem in the mid-year reporting I have

suggested. Parents and students are not (in theory) party to the attainment

data that determines the target action segment, so they cannot engage in

altering behaviours based around the bell curve as they cannot see this data.

However, students would end up making some level of assessment of this

themselves (as they begin informally sharing raw assessment data amongst

themselves). Parents may reject the entire proposed system here exactly because

it shields information from them which they want to use. And, of course, we now

face the other risks of the students not being aware of low attainment that

does need action.

Overall, my conclusion is that I

would stave off providing attainment ‘word’ data (and go with my mid-year

action reports above) early on the in the year, especially in new courses. The

risks of providing cohort-referencing here are greater, in my view, early on than they are later on. I would definitely consider personalised communication for those who

need the negative surprise though – we can contact only certain segments

remember. We don’t always need to contact them all. (See Principle Five) This

would need careful implementation, but might provide a middle way to address

this problem. I don’t think there is a way out of providing attainment ‘word’

data at the end of the year though, the risks and issues of not doing this are

greater than doing so and we have to just accept that people will do what they

will do with the surprise they receive.

One aspect you could tweak would be

the categorisation of prior attainment into the four word categories (it would

be technically possible try to try to create more negative surprises than a

very simple cohort ranking would allow, as you control the boundaries and

language), but this is ethically, motivationally and practically

problematic.

You probably are thinking about other

loose ends I’ve left hanging like, how do you know how much progress was made

from the start of the course until the middle if you’ve not done a baseline

assessment? How can we identify and support underperforming teachers in all

this? What about the reliability and suitability of the assessments in the

first place? Many further questions remain to be answered.

I am not yet sure I have settled upon

a finalised position in my own thinking on this yet, and I write this blog

simply to share some of my thinking and to encourage further

thinking/research/idea sharing so we can reach and improve collective

understanding of what best practice looks like with regards to reporting and

home-school communication in general.

I do believe we can learn some

lessons from the highly refined communications of CRM professionals, but we

also need to carefully evaluate the transfer of concepts into our (quite different) domain and specific contexts. There is little research available in the area of

reporting from what I can find, so we cannot just ‘turn to the evidence’ on

this one for now. And I am not entirely sure that research will end up being

especially conclusive anyway as there are so many variables involved here, and

the impact of any measures used may end up only being very small anyway - it will be

interesting to see what happens in this respect.

I look forward with hope to the

wiser, better read, more creative and more experienced amongst you applying

yourselves also to this issue. To you continuing to refine and perfect some

suitable solutions to ensure assessment and reporting support the great strides

we make as a profession in teaching, learning and curriculum development.

We cannot overhaul some parts of the

jigsaw whilst leaving other pieces untouched as the picture won’t look right

anymore and all the pieces will no longer connect together properly. This is where

I feel we are now in our journey, so I hope you will join me in attending further

to these particular jigsaw pieces and I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

[i] 1.

Sorry Teacher Tapp, I haven’t always kept up!!

[ii]

2. I have used the term ‘parents’ here to reduce to cognitive load for the

reader in a text-heavy piece. Of course, this also relates to carers and all

others in a child’s home life who would receive their school report.

[iii]

3. Mark Roberts - @mr_englishteach

[iv]

4. Professor Becky Allen – Blog posts on grading. https://rebeccaallen.co.uk/2019/04/24/grading-game-part-i/

[v] 5.

David Didau – Blog posts on curriculum as a progression model. https://learningspy.co.uk/assessment/why-using-the-curriculum-as-a-progression-model-is-harder-than-you-think/

Comments

Post a Comment